Game 4: A boy’s first game

New York Yankees vs. Philadelphia A’s

Yankee Stadium, Bronx, NY

August 20 or 21, 1949

My first memory of baseball is reading the NY Daily News account of Gene Bearden’s heroics in the Cleveland Indians’ defeat of the Boston Red Sox in a one game playoff to get to the 1948 World Series. The following year I was a Yankee fan, listening to games on the radio, reading game accounts for all the teams, the box scores, and the stats, again in the Daily News, with all the devotion of a religious acolyte. Sometime that summer, Dad suggested we go to a game. My father was also a devoted Yankee fan (I believe because of his great admiration and identification with Lou Gehrig—both Gehrig and my father were of German descent, raised in New York City, and attended Columbia University), so there was a total united family front on who to root for.

Our routine that day was as it would always be over the following five-six years. Dad drove into the Bronx and parked the car north of the stadium on the Grand Concourse; we then got on a D Train to the stadium. This, I came to understand, was to avoid the clusterfarg that was parking by the stadium (and its attendant exorbitant fees).

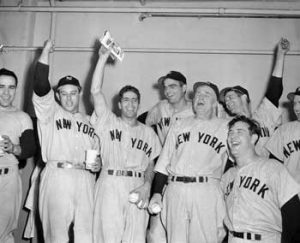

A long time ago, I was going to write a brief essay about my first impressions of my first baseball game, but, then, in no time, I read about a half dozen magazine pieces all of which said what I would have (it was the time of the great, florid, fathers-passing-onto-the-sons the love of baseball nostalgia moment in sports writing), and so abandoned the idea. But I am still taken by the rhapsody of the senses on that first day: the urban hurly-burly of the elevated train, crowd, and the street vendors hawking food and souvenirs (I remember the rush of desire for the 8X10 glossies of my favorite Yankees: Rizzuto, Berra, Henrich, and, most of all, Joe Di Maggio, my first sports hero); the gray cavern inside with the pungent smell of beer and hot dogs, and then heading up the tunnel to the seats and seeing the greenest piece of earth I had ever seen In my life (an illusion no doubt created by its contrast to the urban drabness of its surroundings).

I do not remember anything about the game; I saw Joe DiMaggio, and that was all that mattered. And I remember A’s owner and manager Connie Mack, because unlike the other baseball managers, he did not wear a uniform; instead he was dressed in a dark navy blue suit, white shirt and blue tie—more like a football coach than a baseball manager.

It was a grand baseball summer, an exciting pennant race between the Yankees and the Red Sox, which was not resolved until the last two games of the year—the Yankees beat Boston both games to win the pennant by one game. I remember sitting by the radio at the kitchen table that last Sunday cheering them on with Mom and Dad, now myself a member of that tribe called sports fans.

And it was a grand decade too. I had three teams to watch and listen to, brought to me by some of the finest sports broadcasters of all time: Mel Allen (the Yankees); Red Barber and the fledgling Vin Scully (the Dodgers), and Russ Hodges and Ernie Harwell (the Giants). I saw the Bobby Thompson “shot heard ‘round the world” homerun on TV, and I saw my team win five consecutive World Series, which I came to understand was far from the usual estate of fandom (I learned this painfully as a New York football Giant fan during the years in the wilderness from the mid 60s to the 80s).

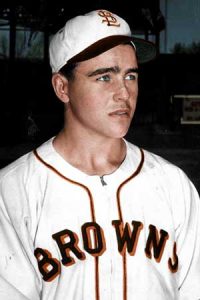

I also learned that my team was hated by many. I lived in a middle class neighborhood most of whose residents were Dodger fans, and all the kids I played with were Dodger fans. I suspect many of them thought my parents and I were putting on airs and had pretensions of being better somehow by being Yankee fans. In time, bragging rights became a burden and a source of guilt. Good Catholic boy that I was, I did penance by becoming a secret fan of the St. Louis Browns, a perpetual cellar-dwelling franchise with few talented ballplayers. I had little to cheer except for Ned Garver’s 20 wins in 1951 while the team lost 102—a feat described by one wag as just behind Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead. At a Sunday double-header versus the Browns the following year, I persuaded my dad to buy me a Browns cap. An almost stereotypical loud and brash New York fan sitting in front of me, when he saw what I was wearing, incredulously asked, “You rootin’ faw da Browns?” I meekly nodded, and received the look of pity and condescension usually reserved for the village idiot.

My interest in baseball and all sports began to wane toward the end of the decade as I wandered through the minefield of adolescence. Other interests began to impinge on my devotion—the usual (girls and books and idealistic zeal) and the more arcane (jazz). My waning interest in baseball was intensified by the Giants and Dodgers moving to California following the 1957 season, an event, which more than anything else symbolized the end of the idyll of my childhood and made the game smaller in my estimation. My paternal grandfather and uncle Matty were devoted Dodger fans; my paternal uncle Bill a Giants fan. I spent many a summer afternoon watching both teams with them. Now when I went to my grandfather’s home in Sunnyside, Queens in the summer the radio and TV were silent—no Dodgers meant no baseball. Uncle Matty would die five months before the move was announced; my grandfather, almost two years after the last game was played at Ebbets Field and two months before the Dodgers would win their first championship in Los Angeles. Their deaths and the move west of the Dodgers and Giants were my first lessons in the transience and impermanence of life.

It would be a decade before baseball in particular and sports in general would re-enter my life, and only then would I resolve the Yankees-Browns dualism.