Game 9: The real dream team

New York Knickerbockers vs. Los Angeles Lakers

Game 7, NBA finals

Madison Square Garden, New York City

May 8, 1970

It was my paternal Uncle Billy who introduced me to basketball. It was his sport growing up, and, in fact, the game is the reason he became a beloved member of my family: he and my dad were teammates on a Queens, NY, rec league team, and Dad introduced him to his sister. Although it was not the first game I watched or listened to, my earliest memory of a basketball game is a TV viewing with Uncle Billy of an NIT tournament game from 1952 with the Tom Gola-led LaSalle team, the ultimate winner of the tournament.

My first years as a Knicks fan were good ones: they went to the NBA finals three years running (but lost all three, the first to the Rochester Royals; the last two to the Minneapolis Lakers, the dominant team of the early 50s). They had a talented team led by Harry Gallatin, “Sweetwater” Clifton, Dick McGuire and Carl Braun, and coached by the New York basketball legend, Joe Lapchick. And then there was the bonus of Knicks radio broadcaster, Marty Glickman.

Glickman had the most beautiful voice this side of Red Barber; where Barber’s was Southern mellifluousness personified, Glickman was pure Brooklyn, New York, but just as smooth and soothing. A former high school and college football and track standout and member of the 1936 Olympic track team, Glickman, in essence, created the language of basketball announcing, and for the first time the game became vivid for a radio audience. You could see the court, the way Barber and others allowed us to see the baseball field over the radio. And I loved his catch phrases like “Good, like Nedicks,” when a player made a shot (Nedicks, a New York hot dog and orange drink chain, was a sponsor, and a long time favorite of mine along with the Horn and Hardart cafeteria).

Glickman was not compensation enough for the Knicks teams that were to follow in the late 50s and early 60s. From mediocre to truly awful, they suffered a dearth of talent (Kenny Sears was decent, and Ritchie Guerin, who played his college ball about a mile from where I grew up at Iona, was very good) at a time when one of the great sports dynasties was in existence, the extremely talented Bill Russell-led Boston Celtics who would win 11 titles in 13 years.

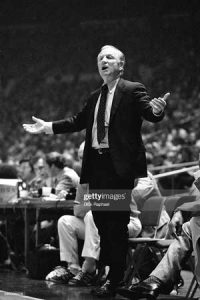

Hope for Knicks fans began slowly but surely to build in the mid 60s with a steady stream of good draft choices—Willis Reed, Dave Stallworth, Cazzie Russell, Bill Bradley and Walt Frazier, and the acquisition via trade of Dick Barnett. But disappointment continued until the 1967-68 season, when two alterations put the team over the top—Red Holzman became the coach, and midway through the season, the Knicks traded for Dave DeBusschere, who was the missing piece in the starting five.

Holzman molded the team into a pass-first team that honored the fundamentals of team play, and a tenacious defensive team (they were particularly adept at two-man traps). Basketball, at its best, is the ultimate team sport: five individuals, working together, enhancing each other’s strengths, covering for each other’s weaknesses. The Knicks raised these principles to their zenith, which filled me with an almost religious ebullience when I watched them play.

The following year in the playoffs, they defeated the East champions, Baltimore Bullets, in four straight games, but lost to the Celtics in Bill Russell’s last hurrah in the division finals. Walt Frazier had a nasty leg injury (I remember in one game, watching him pound his thigh with his non-dribbling hand as he brought the ball up court), and that probably cost the Knicks their chance to win.

The following year, they defeated the Bullets again, this time in a hard-fought seven-game series, two of which I was privileged to see in person at the Baltimore Civic Center in the company of my best friend from college. It featured titanic duels underneath between Reed and Wes Unseld and DeBusschere and Gus Johnson, and on the outside between Frazier and Earl Monroe. They defeated the Bucks in five to go to the finals against the Lakers.

The Knicks and Lakers traded wins every other game. The third game had an unreal ending: Jerry West took the inbound pass from Wilt Chamberlain (who wasn’t called for the fact that he took a step onto the court before he passed) with seconds left. West threw up a 3/4-court heave, which went in and tied the game. But the Knicks won in overtime.

Disaster struck in the fifth game, which I listened to with great difficulty at home. This was before the NBA was a big deal, and not all the games were televised nationally, so I had to listen on the radio. As I was over 200 miles from the New York station broadcasting the game, I had to pick up the radio antenna and hold it up over my head near the window to get reception. Willis Reed fell to the court with a leg injury late in the first half. Without him, it was possible for Chamberlain to just go wild inside and kill the Knicks. Instead of going to their vastly inferior backup center, Holzman went to a small, active three-forward lineup of DeBusschere, Bradley and Stallworth playing off Chamberlain hide-and-seek fashion, then double-teaming him when he got the ball. It confused and rattled the Lakers and the Knicks pulled out an improbable win; I was elated, and my arms were exhausted. Game six had Holzman revert to using his backup center, and Chamberlain destroyed the Knicks, leading to a game seven and the question on every Knicks fan mind: would Willis Reed be able to play, or would injury once more deny the Knicks their first championship?

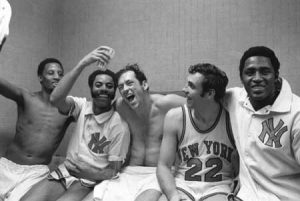

The Knicks practiced before opening tipoff without Reed, and were congregating around their bench when Reed came out of the tunnel to thunderous applause from the Madison Square Garden crowd. You could see he was hurting, but he leaned into Chamberlain on the Lakers first possession making it as hard as he could for him, and Chamberlain missed his first shot. Reed limped down the court, trailing his teammates, took a pass, and hit a medium jumper. The crowd roared again. Again the Lakers failed to score, and Reed proceeded to hit a second jump shot. The Knicks called timeout, and that was all for Willis. But it had its effect. The Lakers, particularly Chamberlain, looked defeated just minutes into the game. Walt Frazier then proceeded to have the game of his life: 36 points, 19 assists and five steals.

My friend and I celebrated until the saloon closed down, and I had my second glorious fan triumph in eight months, a happy façade for the failure that my life was soon to become.

The following year, the Bullets finally overcame their New York jinx, and defeated the Knicks in the eastern conference finals. The next year, the Lakers got their revenge, and won the finals handily in five games. But a different Knicks team (Jerry Lucas replacing Reed, and Earl Monroe, traded to the Knicks from Baltimore because the Bullets could not meet Earl’s salary demand, in place of Barnett) beat the Lakers in 1973 for their second and as of today, last, championship.

The team then slowly devolved into the middle of the pack, then got awful, and I lost interest. I was spoiled by the basketball that they played in those wondrous years 68-73. The Knicks had one brief run at the championship in the early 90s, but those Ewing-Starks-Pat Riley coached teams played the game, to use the Italian insult for bad chefs, like shoemakers, and I could not muster interest. Since then, it has gotten worse, and I ceased to care long ago.